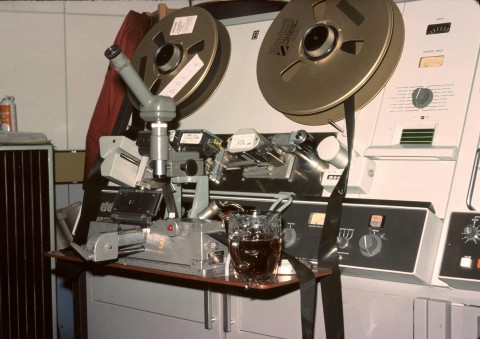

(Photo copyright John Burkill, no reproduction without permission – the photo must have been taken after lunch – well during VT’s standard liquid lunch!)

The Videotape area adjoined Telecine, so I got to know the VT staff, and something of the operation even before I had chance to actually work in the area. In 1974 there were just 2 VT machines, Ampex VR2000 2 inch. These were known as Quad machines as the recordings were made using 4 rotary heads across the width of the tape, quadruplex recording. VTA was optimised as a play in machine, and VTB as an edit machine. Both were capable of being used as stand alone recorders or players with the studios, and could be used for simple assemble editing, but more usually one was used as a master recorder and the other as a backup at that time, as there was no way of knowing until playing back, that the recording had been successful. There was no off tape monitoring, and a head-clog at the start could render the whole recording useless.

At that time John Lannin, and Tony Rayner were the senior editors, with Ian Collins, John Burkill, and Steve Critchlow making up the remaining VT team. What many people working in TV today fail to realise is that VT machines then needed careful alignment for every tape, and that they required a ten second run up in order to lock up fully synchronously. (Occasionally even 10 seconds was not long enough!). Although cut editing of tapes had been occasionally done in Black and White days, it was not accurate enough (normally) for colour recordings.

There were exceptions. I believe there was a unique recording that had somehow had tape damage that caused the tape to snap, (the transverse rotary heads were not unlike a circular saw if there was a nick in the tape) and John Burkill performed a cut edit to join the tape back together. This involved applying Edivue, a suspension of fine iron particles in solvent, to the tape to develop the tracks and the edit pulse, on each side of the damaged area. Then using a travelling microscope to locate the correct point and place it precisely in the edit block, cut the tape either side of the damage, and finally splice together using splicing tape. Normally a cut edit like this would not play without some glitching, but on this occasion it played almost as well as a standard electronic edit. Subsequently some months later I also had to repair a tape in this manner, and achieved a similar result!

VT was a noisy area. The rotary heads ran at 15,000RPM, and there being 4 heads on the drum a new head entered the tape past the edge 1000 times a second. Added to that the rotary heads were run on air bearings, which was supplied with compressed air, and created a vacuum for the vacuum guide to hold the 2 inch wide tape in a circular arc. The machines did have their own air compressor which could be used (adding even more noise), but generally used compressed air from a central compressor housed away from the area. The same compressor fed airlines to the Telecine cubicles to allow for blowing dust out of the film Gate. So what with whirring heads, hissing air and other general mechanical noise, the monitor loudspeaker was generally quite loud in order to hear the sound.

The VT machines needed careful looking after to get the best out of them, and tended to drift as they warmed up. So the normal course of action for the switch on man was to switch on the machines, check that the basic systems were working, then go and have a coffee while the machines warmed up. There was always a 1/2 hour line-up period scheduled before each booking, to allow time to make the fine adjustments required for the tape. In an edit session using several different source tapes, line up could take up quite a lot of the time. If the tapes came from the same recording session, a quick 2 to 5 minute adjustment may be all that was required, but where there were tapes from several different source machines, (often the case for Pebble Mill at One), 10 – 15 minutes or longer could be required if there was a particularly awkward tape.

Finding the required place on the tape could take a while also, as there were no pictures in shuttle. Tapes were logged on a card that was kept with the tape. The machines had a counter which was calibrated in minutes and seconds, and was surprisingly accurate considering it was a friction drive. On loading the tape, one had to remember to zero the counter, otherwise the times would not correspond to what was written on the card, or worse you could end up logging the incorrect times on the card for a new recording. Tapes were re-used quite a lot, as the tape was expensive, and in order to ensure a clean tape they were put into a bulk eraser (nicknamed the fish fryer on account of its height shape and the perforated roll lid.) It took about 20seconds to erase the tape, so you had to be certain that you had the right tape, and that it really was ok to wipe it, before pushing the button.

Some compilation tapes were reused without first erasing them, which could sometimes cause confusion when remnants of a previous recording were left in between two logged items.

Ray Lee