(Below is Simon Farquhar’s obituary of David Rose, which is published in The Times today, 24th Feb 2017. Thanks to Simon for sharing the full copy of his article.)

When David Rose was appointed the BBC’s Head of English Regions Drama in 1971, with a noble brief to “find new writers in the regions and nurture them”, the Head of Plays waved him off to the new Pebble Mill studios in the badlands of Birmingham saying “you will come to our weekly meetings, won’t you?” Shrewdly, Rose replied “thank you, but no. I don’t want to know what you’re doing, and I don’t want you to know what I’m doing”.

It was typical of what made him an adored man, a wise and altruistic professional with a Father Christmas beard, a twinkling eye and a boundless enthusiasm for drama, stories and, crucially, storytellers. Softly spoken and broad minded, he was a quiet giant who gave a voice to those with new and dangerous things to say, driven, unlike many other pioneering forces in television drama of the time, not by politics but purely by principles, and known to chew his handkerchief in anxious moments. His ten years at Pebble Mill are now the stuff of television legend and a wonderland for the tv historian to explore. On his watch, that building became a powerhouse of innovation and unpredictability; young talent such as David Hare, Willy Russell and Stephen Frears made the place “the British film industry in waiting”.

Born in Swanage, Dorset, David Edward Rose and his sister Daphne lived over the jeweller’s shop his parents ran in the High Street. He inherited their love of music and his mother’s interest in amateur dramatics; his uncle had also set up the first cinema in town. After Kingswood School in Bath and war service with the RAF, during which he undertook 34 flying missions in a Lancaster Bomber, he took a year out in Cannes. After watching Michael Powell explaining film rushes at the end of a day’s shooting on The Red Shoes, he aimed at becoming a director. He studied at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, then worked in repertory theatre for five years, firstly as an actor at the Royal Hippodrome in Preston, where he met his first wife, Valerie Edwards, and then as a stage manager at Sadler’s Wells, before joining the BBC in 1954 as an assistant floor manager.

In his first week, he worked on the now-legendary Rudolph Cartier production of 1984. He later transferred to Elwyn Jones’ Dramatised Documentary Unit, where his first credit as a television director, Medico (1959), about the service that offered emergency medical advice to those at sea, won that year’s Prix Italia. Rose was fond of relating how, after the prize giving, he said to a man at the bar “Hello, I’m David Rose, a producer”. The man replied “hello, I’m Samuel Beckett”. Rose met Gracie Fields on the same trip, and said he always regretted not introducing them.

The following year he launched Z Cars, a series it is impossible to overstate the importance of in television history. It brought a new immediacy to television drama and believed that “a police thriller could be a work of art”, something television is only now, over half a century later, realising again. The pressure of live broadcasts was immense; on one occasion, when actor James Ellis had broken his foot, Rose, out of shot, carried him from one high stool to another, to give the illusion that the actor was delivering his lines standing up.

Director of Television David Attenborough would later say that appointing Rose as Head of English Regions Drama was one of the best decisions he ever made. The triumphant debut, Peter Terson’s The Fishing Party (1972), a story of three Leeds miners on holiday, was an authentic, unpretentious, home-grown treat. After its broadcast, Managing Director of Television Huw Wheldon telephoned Rose and said “if that’s what you’re going to do boyo, that’s alright by me”.

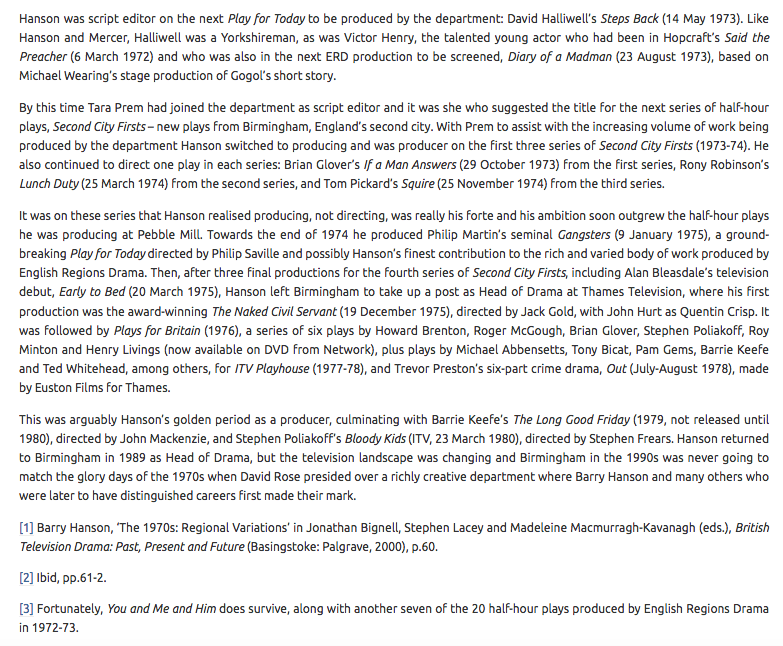

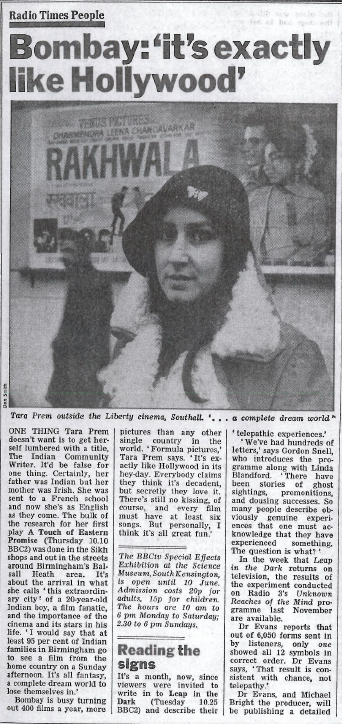

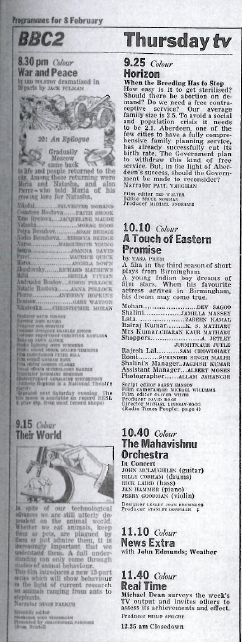

Plays with fire followed this beguiling start; incendiary half-hours such as James Robson’s magnificent Girl (1974), in which Alison Steadman and Myra Francis gave British television its first lesbian kiss, were history in the making. A Touch of Eastern Promise (1973) was the first drama on British television with an entirely Asian cast; the soap opera Empire Road (1978) was another first, written, acted and directed predominantly by black artists, set in one racially diverse street in Birmingham.

Nowhere on television before or since has the “right to fail” principle been so fearlessly executed. Rose loved discovering writers with no screen experience; “some people thought this was mad, but I thought it was great. They come with no baggage”, he explained. “Every day of my working life depended on writers. The BBC used to do audience satisfaction surveys, and you had to score a figure as close to 72 as possible to keep the bosses happy. I didn’t agree. If it was a low figure, I thought that was good. I don’t want to make it easy for the viewer. I don’t like them to know what’s coming”.

Although some of Birmingham’s output was commissioned by London, there was a kitty of development money which allowed him to make things without having to ask permission. This was how he got something as wild as The Ken Campbell Road Show on the air, and other works that could be called courageous and adventurous; he knew a keen as mustard young director like Matthew Robinson was just the person to hand a script like Eric Coltart’s Doran’s Box (1976) to. “I don’t understand it, it’s about a man who shoots at aeroplanes”, Rose said. Whatever was inside that puzzle box remained a mystery for the small number of head-scratchers who watched the finished piece, but we had fun trying to find out.

Rose had far more respect for his audience than his superiors. He had to fight constantly for his survival within the BBC, and had his fair share of hot potatoes: Philip Martin’s savage Gangsters (1975), Watson Gould’s blistering feminist attack on a patriarchal society, The Other Woman (1976), Malcolm Bradbury’s concupiscent The History Man (1981) and a planned-then-banned production of Ian McEwan’s Solid Geometry. But there was also Mike Leigh’s Nuts in May (1976), Alan Bleasdale’s The Black Stuff (1978) and the film he was most proud of, Penda’s Fen (1974) by David Rudkin, one of the richest and most sophisticated works ever produced for television. At its simplest, the story of a teenage boy’s awakening to the English landscape surrounding him, its potent blend of folklore, folk horror, questions of personal and national identity, environmental concerns, sexuality and religion made for a bewitching brew, interweaved with the music of Rose’s favourite composer, Elgar.

The days of pockets of anarchy at the BBC were coming to an end as the 1980s ushered in new threats to autonomy and artistic integrity. Rose was two years off retirement when Jeremy Isaacs invited him to become Head of Fiction at the new Channel 4.

It was an Indian summer for him. In his first year there, he produced 20 feature films; the previous year there had been just 21 made in Britain as a whole, only two of which were British. Over eight years, he approved the making of 136 films in total, the advantage over the films made for the BBC being that some had the chance of a theatrical release. High profile successes included My Beautiful Launderette (1983) and Mona Lisa (1986). And fiction didn’t only mean films: he also commissioned a soap opera like no other, Brookside (1982), a breeding ground for writers such as Jimmy McGovern and Frank Cottrell Boyce.

Some disapproved of Film on Four, claiming it betrayed television drama by diverting funds into a moribund film industry. But it allowed strange, wonderful work to be produced and gave a transfusion of faith into British movie-making. As we salute the arrival of T2 Trainspotting we should remember that it, like its predecessor, was backed by Film4. In 1987, Rose received the Roberto Rossellini Award in Cannes for Channel 4’s “services to cinema”, a remarkable and deeply significant achievement.

His appetite for new people and places was a personal as well as a professional virtue; in his later years, having read that if you make a new friend you extend your life by a week, he made a point of getting to know new people, be it in the street, at a bus stop or at a concert. Director Tony Smith says that “he could be irascible, infuriatingly dilatory, he said ‘garn’ and ‘goff’ instead of ‘gone’ and ‘golf’. He was patrician, but a benevolent and self-challenging one. And we all loved him”.

His domestic life was a busy business: married three times, lastly to producer Karin Bamborough, who had been his assistant at Channel 4, he made his own huge family as harmonious a place as Pebble Mill had been; domestic life was often carried out to a classical soundtrack which he would usually be caught conducting around the house or at the wheel of his car. His passion for music and drama was passed on to his nine children, one becoming a jazz musician and another becoming a producer. At 89 he made his debut short film, Friend or Foe, which explored his experience of Parkinson’s Disease. It won him a Mervyn Peake Award.

When he received a BFI fellowship in 2010, Head of Film and Drama at Channel 4, Tessa Ross, announced that “you are in my head all of the time, as I try and protect that precious place”. Tony Smith recalls how “towards the end of his time at Birmingham he took a sabbatical. Some months after his return, he asked me: ‘English Regions Drama – have we succeeded, really?” I answered him at length, ticking off all the positives. He made no comment. As I was leaving, I said, ‘You know, when you were gone, we were afraid you wouldn’t come back’.

He had returned then, but he will never be replaced.

David Edward Rose, producer, born 22 November, 1924; Swanage, Dorset, married 1st, 1952, Valerie Edwards (d 1966); three sons three daughters; 2nd, 1966, Sarah Reid (marriage dissolved, 1988); one daughter and one stepson, one stepdaughter adopted; 3rd, 2001, Karin Bamborough, died Hackney, London, 27th January 2017

Simon Farquhar